Mobile Museum

Revealing the Written Reality of the Past

Welcome to my Website – and also the associated Website!

History and education have been my life, both as a curator and as an historian. I believe in supporting our written historical records with the use of objects (or artefacts), even using replicas and reconstructions to discover how things were done and if they could be done. We only have “things” and records (which can be biased) but what we really want to know about are people and places. I believe that using good historical re-enactment is also of great value when seeking to understand “the past” and that understanding the past matters.

So, over the years, I have researched and written a good deal, seeking discoveries, refusing to believe that which cannot be proven, questioning the blind beliefs (often created in Hollywood or on films) which are so often fed to us and presented as “facts”. It is this refusal to blindly repeat (in default of sound evidence) what I have been told that has made me “the most hated historian” among historians.

Well, surely we all want to know how the present came to be what it is?

So I present two parts (in this chirograph):

1 My Publications

2 Some of my craftwork and reconstructions

I hope you will enjoy them both

MY PUBLICATIONS

Most people have heard of Domesday Book but few know what it is and, up to now, no-one has actually been able to read it.

Of course if you ask what it says you will be told (by “experts”) that they can read it, because they are clever and academic, but, in fact, they can’t! They can only translate it but none of them know what the mass of statistics is saying and they cannot produce any statistically significant evidence: for all their claims they have no proof.

As a result much of our English history of this period, the eleventh century, has been created to support a series of assumptions and assertions which, themselves, cannot be proved in any way. Fairy-stories and Hollywood indeed, not history!

Back in 1978 I discovered the Key to reading these Domesday statistics, the Key (if you like) to breaking the “code” of Domesday Book. Immediately vested interests did everything they could to silence and discredit me: I should not be believed, I was “rocking the boat”, I was insane and they were determined I should not publish.

In 2009, being by then retired, I finally published my findings myself, but historians were unprepared to accept the “olive branch” I was offering in 2014. I wrote again, establishing myself as the most hated historian in England.

I was actually telling people that they could read Domesday Book for themselves, that they were not, as the clever people had told them, “ignorant” or untutored but were quite capable of discovering the truth and the facts for themselves. Anyone can create a picture, for themselves, of almost any place in England almost 1,000 years ago and because the pictures which emerge contain very surprising economic, fiscal and demographic evidence I then wrote this further set of case-studies (or essays) in 2016.

In 2019 Pen & Sword (Frontline) published my analysis of the Bayeux Tapestry which, like Domesday Book, is also a unique Anglo-Norman creation of immense historical value. Being able to read Domesday Book and so to then see what its statistics say about the invasion area, people and landscape made it possible to put the Tapestry’s visual message into context; I had also deduced and so observed that the top and bottom margins are not just “decorations” but provide a universal picture language which also, once “decoded”, tells a story; a story which supplements that shown on the main frieze of the “tapestry”, a language which even illiterates could read. So the total Tapestry picture is actually in three parts, viz the main frieze, the picture language and the Latin text (which was added afterwards).

Following this in 2020 the same publishers invited me to write the story of the Norman Invasion. Well, it should be obvious to anyone that King William could not have spent the next twenty years fighting-off successive foreign invasions and putting-down Norman insurrections without the assistance of English fyrdmen and shipmen; just as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles actually tell us. Furthermore, we have all been told that William seized the throne in 1066 but in fact the written evidence says that the (surviving) English Witan invited him to become King of England. Moreover true feudalism was demonstrably an English creation, one consequent upon an efficient system of taxation. Once again Domesday Book, when read, provides supporting evidence for all these things and for a picture of integration very different from the distortions and fairy-stories we have so often been fed.

During the Covid emergency the same publishers kindly invited me to write about the “Battles that Created England, 793-1100”, in other words to present just how a single English nation emerged as a consequence of a succession of foreign raids and invasions, finally to become the economic envy of western Europe. This book was published in 2022.

Whilst most historians simply see the recorded events as a series of unrelated disasters and fortuitous episodes the written records and the archaeology, when viewed from a military perspective, do actually follow a coherent pattern, one related to developing strategies and tactics (and some technologies) whilst the necessary logistics tell us a good deal about English industrial capacity and why the Vikings came, and especially about the emergence after 991 of a unique system of taxation. (In fact the basic foundations of our modern national system of taxation). Together with feudalism this fiscal system formed the final “mortar” which bound Normans and Englishmen together to ensure a Normans succession and so to form our Middle English, medieval, society in the following century.

So, if you have an open mind, believe in scientific methodology and enjoy a challenging read, here is a collection of books for you. There is, of course, one caveat. If (like so many people) you do not like statistics (or this methodology) then the books dealing specifically with Domesday Book may seem hard going – but being able to read its evidence is essential to the understanding of other surviving, written, evidence. It is the failure to read the massive and impartial evidence of Domesday Book that has resulted in so many historical distractions, novels and fairy-tales for this period, inventions which were taught to us as “history”!

And, I almost forgot, but in 2021 I published a synoptic analysis of the Domesday statistics and units presenting them as a detective story or a treasure-hunt. This should be a much easier read, especially as it is quite brief and it has some handy tables to save having to make lengthy calculations, so maybe it is the best place to start? Yes, read this synopsis first!

By the way, the little chap on the cover of this book is Titivillus, yes, our opening “imp” who you have already met. If you want to know his relevance (and he really is engaging) then look him up. He has been around for a long time and he is the reason why academics make mistakes. It is his job, you see, to lead them astray!

2 SOME OF MY CRAFTWORK AND RECONSTRUCTIONS

Working Replica of the Saare (Saxon) plane in staghorn and bronze

Working replicas of Roman jack and foreplanes and a bronze Roman tri-square (maximum length 6 unciae pes Drusianus)

Interior of my toolbox veneered in the 18th century manner to advertise my skill. Before the advent of “bits of paper” this was the way to proclaim proficiency in practical form. The “till” lifts out to give access to sets of planes beneath.

The trick with marquetry is to cut a “packet” of different veneers all sandwiched together and then separate them, so providing a variety of colour combinations and pictures for use on other boxes/objects as well.

Scabbard of red leather and silver mounts (made for a Wilkinson Sword presentation poignard). Poignards were worn either separately or on the right of the back when worn with a sword. Before the invention of the “parry” such daggers were held in the left hand in order to parry an opponent’s sword thrusts.

Replica costume of c.1565 using as a pattern the surviving buckskin doublet of Nils Sture (who was murdered in 1567), Venetians (breeches), Capotain (tall hat with “ensign” or badge) and long riding boots of welted (or randed) turn-shoe construction, a form that was just beginning to replace the Medieval turn-shoe. Sword, scabbard, belt and hanger of red leather, silver, iron and bronze, the sword of mid-Sixteenth century German form. The buttons of the doublet are of silver and the button-holes worked in black silk. NOTE that it buttons on the “female” side – because there was no such distinction in the 16th century. Also the left pocket flap is false and the real pocket is on the right and is then covered by the sword-belt check-strap.

A late 16th century costume (the patterns once again taken from surviving originals) which was much cooler to wear in hot weather when re-enacting. The cotton (fostat) shirt with crespines and parchment lace displays equally well as a wide collar or standing in the form of a ruff, and it is cooler when turned down to make a wide collar. Doublet and Venetians are held together by laced “points”, making a complete “fitted suit” and these are hidden by the skirt of the doublet; they are useful holes by which to suspend various necessaries. Of course uniting top and bottom effectively as one garment can be (at times) very inconvenient!

Sword belt, check-strap and hanger of red leather and silver, as worn in the above illustration. The hanger permits the sword to be carried horizontally or vertically (say when climbing a spiral staircase!) according to need.

Renaissance dagger in various materials showing inlay and carved pommel, suitable for less formal occasions and very much a piece of male jewellery rather than a weapon.

A 1/30 scale model of an Iron-Age roundhouse, the rear was left open to show the interior. (I have made a number of such models for museums and exhbitions over the years).

Replica of the earliest surviving piece of European furniture, the folding stool from the Goldhoj burial (a Bronze Age grave). Ash (wood) and bronze pivots with fur seat. (Experimental archaeology). NOTE that the original was made using mortice and tenon joints!

Medieval trestle table (“board”) in oak (seven feet long). This dismantles into five pieces (for carriage). Most of the time such pieces of furniture were covered by white or by embroidered cloths. The oak is all quarter-split to reveal the decorative “ray”.

Replica of a hunting crossbow c.1500 showing box-lock and staghorn “nut”, also the inlays, the long trigger (or “key”) and the lion finial chiselled from steel and inlayed with copper and brass.

Prehistoric lathe. We have turned objects from al least the bronze age but no lathe fragments, so for an exhibition I was challenged to make a lathe without any metal fittings. Using stag-horn centres and a pole lathe I was successful and I even made flint-tipped turning tools as an experiment.

The Romans made shale table-legs of this pattern but in England, where oak was unusually plentiful, they could also have used wooden tripod tables. Another piece of experimental archaeology

Monopodial, revived, neo-Medieval style table, the top veneered with a King and six Counsellors (Witan) in various woods and the shaft (of three engaged half-columns) being marbled. The oak table supports were in the form of gothic spandrels and the base was also oak. (In a private collection).

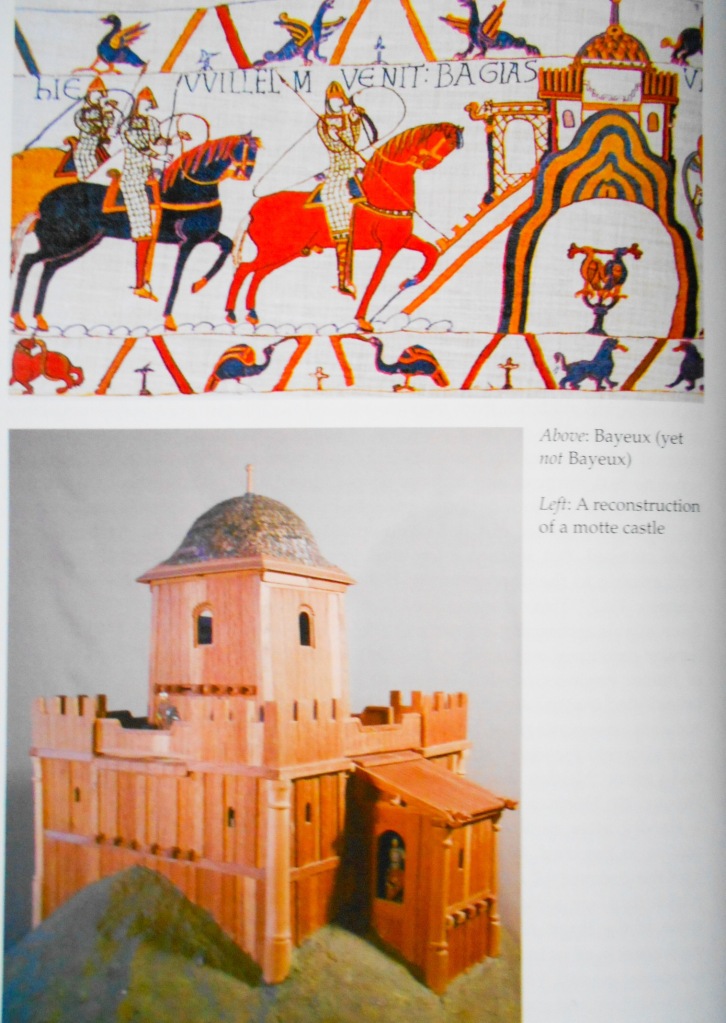

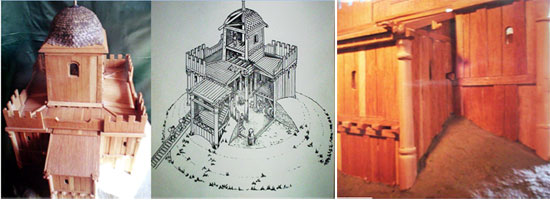

Norman castles are often dismissed as crude affairs but those shown on the Bayeux Tapestry are all individual and very sophisticated. The one shown here at Bayeux (incidentally, the castle here never had a motte!) shows features which we can link to other timber towers and structures as well as to written, archaeological and structural evidence, so this model was constructed to demonstrate how such a “castle” could have been built and partly enclosed on the summit of a “motte”. Building around a shearleg structure and platforms it creates a tower within box work, rather like an aisled hall. It has stave walls, a spire-mast cupola which is both shingled and lead-flashed and, inside, there is provision for an open hearth.

This experiment helps to explain several features later encountered in stone “donjons?” (such as galleries and forebuildings) and it also explains why some castles were actually sunk down into their mottes.

Costume for a girl of 12, scaled-down from the burial dress of Eleanor of Toledo (d.1562); detachable sleeves and laced on either side at the back to permit precise fitting. (Wearing such replicas enables us to experience how people moved and behaved in the past.)

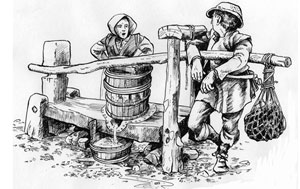

My pen-and-ink illustration for my booklet “Cantles of Tart and Pungete, A History of Essex Cheese”, (2004), (the only surviving Essex cheese-press is in Chelmsford Museum and was my model).

Medieval “lover’s greeting cards” with individual illuminated (handwritten) scripts all bound in leather and fancy papers. Little books like this, containing love poems in English or French, were made in the 15th and 16th centuries and might be termed “Valentine’s cards”.

Two late-Medieval “patrons” or quivers for crossbow bolts (“quarrels”), the “owl” of deer fur and thonging (“Hunts of the Emperor Maximillian”) and the red leather one modelled in relief and tooled over a wooden carcase.

Replicas of Saxon silver in the British Museum = the cloak pin from the Trewhiddle hoard and the Sevington (Wilts) sucket-fork, both originals said to be pre-850 A.D. Presumably the sucket-fork is the earliest example of a fork?

Shotgun re-stocked in American walnut (juglens nigra), the whole fitted, shaped, chequered, oiled and polished. (Not the easiest of tasks)

mobilemuseum22@gmail.com

THANK YOU FOR YOUR INDULGENCE